Buybacks vs. Innovation: The Rise of AI Investment

As U.S. companies shift from buybacks to AI investment, a new era of innovation is reshaping corporate priorities and redefining growth.

Across corporate America, an emerging revolution is transforming how large companies allocate their resources. Instead of handing cash back to shareholders through dividends and share buybacks, many companies are investing large sums in capital expenditures—particularly in artificial intelligence.

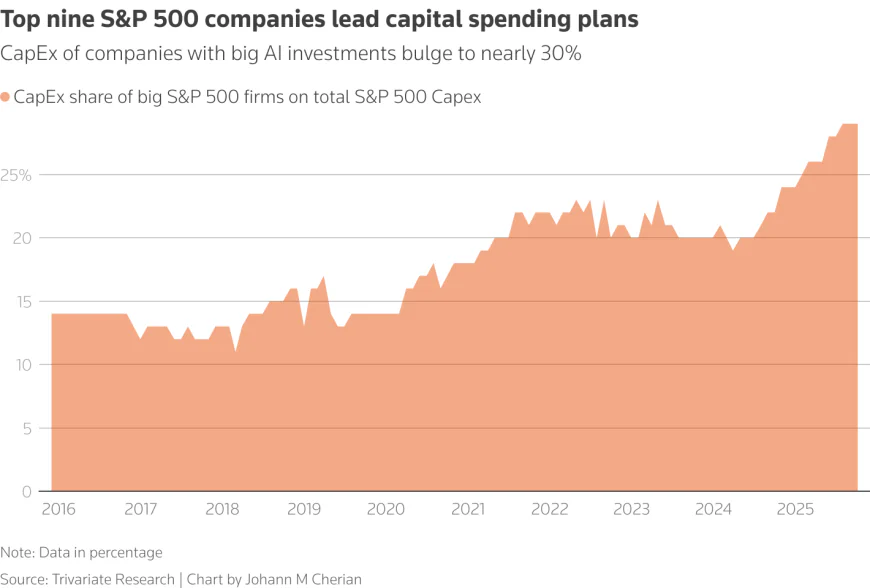

This shift marks the largest redirection of U.S. corporate cash in decades. According to a recent Reuters analysis, S&P 500 companies are on track to spend roughly $1.2 trillion on capital expenditures (capex) in 2025—the highest since Trivariate Research began tracking in 1999.

The nine largest S&P 500 companies—led by Microsoft, Apple, Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, Nvidia, Broadcom, Tesla, and Berkshire Hathaway—account for nearly 30% of total capital expenditures.

In earlier years, companies often focused on rewarding shareholders in the short term — for example, by paying out dividends or doing share buybacks. Those actions provide investors with immediate benefits, such as cash or higher share prices, but they don’t necessarily make the company stronger for the future.

However, in the age of automation and AI, the rules are changing. Companies that invest heavily in technology, data infrastructure, and AI capabilities today can gain a long-term competitive advantage — or what we might call “dominance” — over rivals who don’t.

Rationale For The Shift

A few key ideas help explain what’s happening. Capex, short for capital expenditure, refers to the money spent on long-term assets, such as equipment, technology, property, or R&D—investments that expand a company’s capacity to operate and grow.

It’s the opposite of a shareholder payout strategy, which is how firms return profits to investors. The two classic payout tools are dividends—regular cash payments—and share buybacks, when a company purchases its own shares to boost its value.

For decades, the comfort zone of corporate America was to share buybacks and dividends. It was an attractive venture due to their steady and predictable nature. Buybacks pushed share prices higher by reducing the number of shares in circulation, while dividends offered shareholders a dependable income stream.

However, due to the economic climate of 2025, this has disrupted that very rhythm. The rise of AI has changed the approaches of investors.

What exactly are they investing in? AI spending spans three main areas: infrastructure, software, and talent. On the infrastructure side, companies are pouring billions into data centres, cloud computing capacity, and specialised chips capable of training advanced AI models.

Microsoft, Alphabet, and Amazon alone are expected to account for more than half of all U.S. corporate AI-related capex this year, building vast server farms and leasing power grids to fuel their growing networks. Software is the second frontier.

Firms are developing proprietary AI systems or integrating generative tools into existing platforms, as seen with Microsoft’s Copilot and Adobe’s Firefly. Meanwhile, the race for expertise has sparked a hiring frenzy, as companies recruit data scientists and engineers or acquire smaller AI startups to strengthen their capabilities.

AI offers a route to higher productivity and future-proof relevance. For investors, these projects promise long-term efficiency and growth. AI systems can automate routine tasks, streamline supply chains, improve fraud detection, and accelerate research and development.

JPMorgan, for instance, utilises AI to identify suspicious transactions in real-time, while healthcare giants employ machine learning to expedite drug discovery. These advances translate into cost savings, innovation, and ultimately, competitive advantage. Analysts have described the moment as a “capex renaissance,” where technology investment has replaced dividends as the new signal of confidence.

But this transformation carries significant risks. Building AI capacity demands massive upfront spending—data centres alone cost billions—while returns may take years to emerge. Some analysts warn that the market’s enthusiasm could be outpacing economic reality.

Lisa Shalett, chief investment officer at Morgan Stanley Wealth Management, cautions that by next year, “investors will start pounding their calculators,” scrutinising whether these investments are generating profits rather than just hype.

Smaller firms face particular strain: unable to match the scale of big tech’s infrastructure spending, they risk falling behind or overextending their finances.

Why it matters

The balance between rewarding shareholders and investing for growth defines a company’s maturity and vision. When firms divert cash to capital expenditures (capex), they are betting that innovation will deliver higher returns than financial engineering. “It’s less about shareholder returns at this moment than whether they can develop AI and monetise the opportunity,” said Ohsung Kwon, chief equity strategist at Wells Fargo.

The bet on AI could deliver enormous rewards. Research firm IDC projects that global AI spending will “double by 2028 when it is expected to reach $632 billion”, promising productivity gains across industries from finance to healthcare. By automating repetitive tasks, optimising supply chains, and accelerating research, companies aim to transform these investments into long-term growth and a competitive advantage.

Yet the enthusiasm comes with caution. If too many firms pursue similar AI initiatives simultaneously, overcapacity could emerge — an excessive amount of infrastructure, talent, and software competing for the same outcomes.

The situation echoes lessons from the dot-com era of the late 1990s and early 2000s, when investors poured massive sums into internet startups with little regard for profitability.

Many of these companies failed when hype outpaced reality, leaving only a few survivors, such as Amazon and eBay. In the current AI boom, careful strategy and differentiation will determine which companies reap the benefits and which may face disappointment.

Ultimately, the AI investment boom reflects a fundamental shift in corporate priorities. Companies are no longer content to hand profits back to shareholders; they are betting on innovation, infrastructure, and intelligence to secure long-term relevance.

The rewards could be transformative: faster operations, smarter decision-making, and a lasting competitive edge. Yet the risks are real — overcapacity, unproven returns, and the lessons of the dot-com era serve as a cautionary reminder that ambition must be paired with strategy.