Climate Change in South Asia: Risks, Impacts & COP30

South Asia faces an unprecedented climate emergency, despite contributing less than 9% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Despite contributing less than 9% of global greenhouse gas emissions, South Asia bears a disproportionately high share of the world’s climate-related damage—almost one-third of all recorded losses.

According to Anadolu Ajansı, over the past two decades, floods, droughts, and cyclones have disrupted the lives of roughly 750 million people across the region, highlighting the severe inequity in how climate change impacts are distributed.

The consequences are multidimensional: recurrent floods in Bangladesh and Pakistan destroy agricultural productivity and displace millions, while prolonged droughts in India and Afghanistan threaten water security and food supplies.

Economically, climate disasters erode national budgets, diverting funds from education and infrastructure toward relief and reconstruction, and can trap millions in cycles of poverty.

On a global scale, South Asia’s climate instability contributes to rising migration pressures, food insecurity, and regional tensions over shared water and energy resources.

The growing climate vulnerability of a region poses a threat to global supply chains, trade stability, and humanitarian systems.

COP30

COP30 stands for the 30th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

COP conferences are annual meetings where countries that are signatories to the UNFCCC come together to negotiate, review progress, and set policies to address climate change. COP30 is simply the 30th edition of these meetings.

Countries discuss mitigation (reducing greenhouse gas emissions), adaptation (preparing for climate impacts), finance (funding for climate action, especially for vulnerable nations), technology transfer, and compliance mechanisms.

COP30 is particularly important because it will continue the global conversation under the Paris Agreement, which aims to limit global warming to “well below 2°C” and pursue efforts to achieve 1.5°C.

South Asian countries, as highlighted in recent reports, are advocating for increased grant-based climate finance, easier access to funds, and debt-for-nature swaps to mitigate the impacts of climate change.

South Asia’s approach to COP30 comes at a critical juncture, as the region faces escalating climate emergencies that directly threaten the lives of its 1.8 billion people.

Risks

Without meaningful outcomes at COP30, South Asia continues on a warming path, with catastrophic consequences, including infrastructure collapse, food and water crises, and mass displacement by 2050.

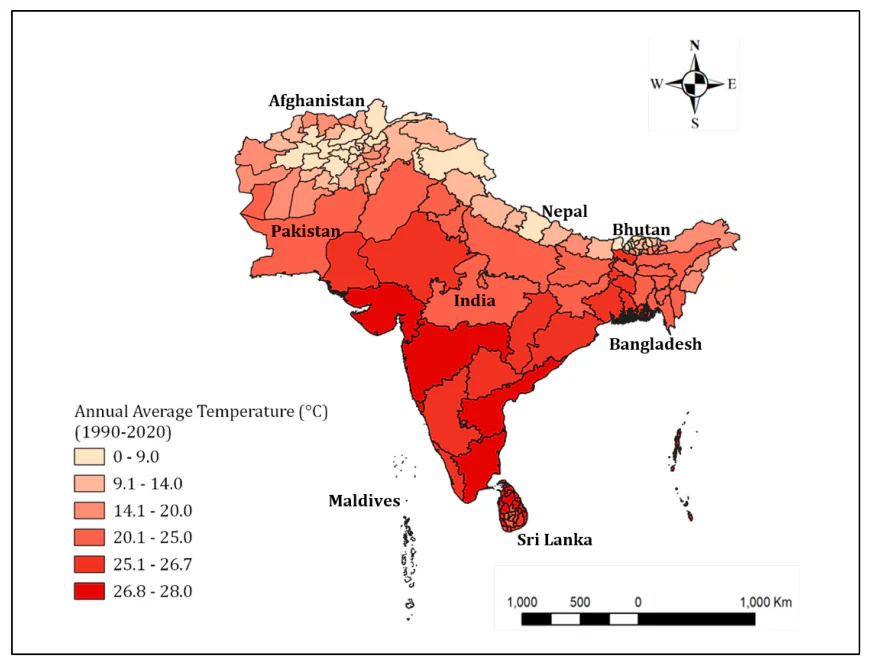

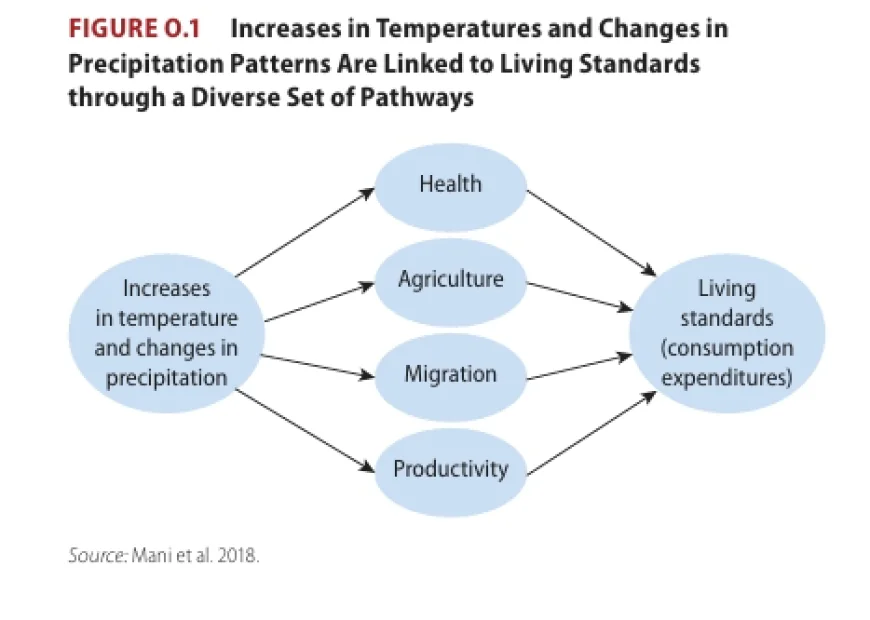

South Asia’s agriculture faces mounting peril as rising temperatures and shifting precipitation patterns undermine already fragile crop systems.

As one study from Springer Link, “in South Asia … it is predicted that the annual average maximum temperature may increase by 1.4–1.8 °C in 2030 and 2.1–2.6 °C in 2050 … with its impact on agricultural production … climate change will bring greater fluctuation in crop production, food supplies, and market prices and will aggravate the situation of food insecurity and poverty in South Asian countries.”

With around half of the region’s population dependent on agriculture, these changes pose a significant threat to livelihoods and regional food security.

Meanwhile, the World Bank warns that “by the 2040s, India will see a significant reduction in crop yields because of extreme heat. … Water for agricultural production in the river basins of the Indus, Ganges, and Brahmaputra will reduce further and may impact food adequacy for some 63 million people.”

In short, warming not only jeopardises yield but triggers cascading risks across the food system—from higher prices to increased malnutrition.

The retreat of Himalayan glaciers and altered river flows present a looming water crisis that could have far-reaching consequences beyond the fields.

The rapid retreat of Himalayan glaciers—the primary water source for major rivers, including the Ganges, Indus, and Brahmaputra—poses significant risks to water security, agriculture, and hydropower across multiple countries.

According to research from the London School of Economics’s Grantham Institute, “the faster melting of glaciers in the Himalayas in recent years will affect the crop production and livelihoods of around 129 million farmers who depend on meltwater from these glaciers.”

This glacial dependence is critical: meltwater supplements irrigation during dry periods and stabilises water supplies in the densely populated Ganges-Indus plains.

When such buffers weaken, South Asia faces floods, droughts, and chronic water scarcity—all of which threaten human health, migration patterns and economic stability.

Rising sea levels and sinking deltas in Bangladesh, India, and parts of Pakistan threaten to displace coastal populations, submerge fertile farmland, and contaminate freshwater supplies with saltwater intrusion.

Meanwhile, extreme heat waves—already among the world’s deadliest—are intensifying, reducing labour productivity, exacerbating health crises, and straining energy systems as cooling demands surge.

Globally, these cascading impacts have far-reaching consequences. Disrupted agricultural production in South Asia can destabilise global food markets, while mass displacement caused by heat and flooding may trigger cross-border migration and humanitarian challenges.

Without swift adaptation and resilience-building, the region risks becoming a climate-change flashpoint with global implications.

Action

South Asia’s call for grant-based, non-debt-creating climate finance reflects both urgency and pragmatism. Many countries in the region, such as Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Nepal, are already burdened with high public debt and limited fiscal space.

Traditional loans for climate adaptation often exacerbate this debt trap, diverting funds away from essential services such as healthcare, education, and resilience-building efforts.

Grant-based financing avoids this by providing direct, non-repayable support, allowing governments to invest in renewable energy, flood defences, reforestation, and early warning systems without worsening fiscal instability.

Simplified access to climate funds—for example, through the Green Climate Fund (GCF) or Loss and Damage Fund—would ensure that smaller or less bureaucratically equipped nations can receive support quickly, rather than being stalled by complex application processes that currently favour wealthier states.

Technology transfer would enable South Asian nations to adopt advanced clean energy systems, sustainable agriculture, and resilient infrastructure, accelerating their low-carbon transitions without prohibitive costs.

Finally, debt-for-nature swaps offer a win-win mechanism: in exchange for debt relief, countries commit to protecting ecosystems such as mangroves, forests, or coral reefs, which serve as natural buffers against climate disasters.

This approach not only reduces debt burdens but also enhances biodiversity and carbon sequestration.

Final Thoughts

Without decisive action at COP30, South Asia risks locking in a warming path above 2°C, with cascading impacts on food security, water availability, health, and livelihoods.

Grant-based climate finance, technology transfer, and debt-for-nature initiatives offer practical pathways to enhance resilience while alleviating fiscal pressures.

By acting collectively and securing the necessary resources, South Asia can protect vulnerable populations, safeguard ecosystems, and prevent the region from becoming a global climate flashpoint.

The time for coordinated, forward-looking action is now, with implications that extend far beyond the regional border