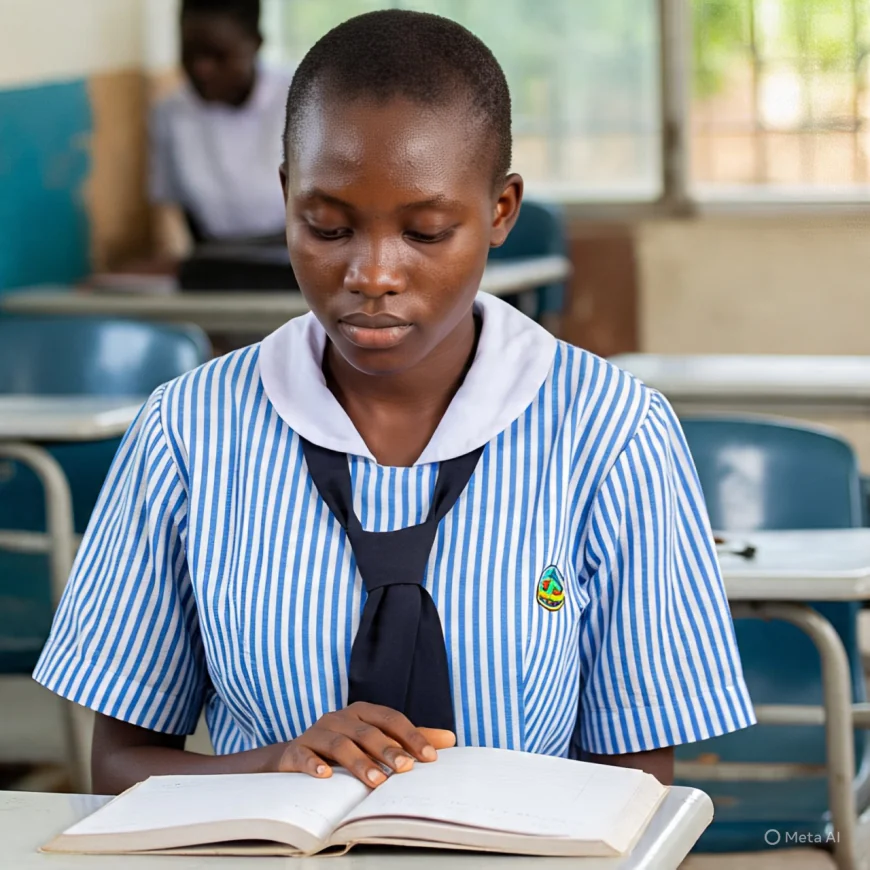

Hair Policies in African Schools: Why It’s Time for Change and Inclusivity

African school hair policies often force girls to cut their natural hair while allowing lighter-skinned students to keep theirs. This article explores the colonial roots, double standards, and the urgent call for change.

Picture this: Two girls in your class, one a dark-skinned African American and the other a light-skinned Filipino-Ghanaian, are summoned to the headmaster’s office on a particularly hot Monday afternoon. Everyone knows why.

They were the only girls who had broken the unwritten school rule: cutting their hair.

The next day, both girls return to school. The African American girl arrives with her head shaved down to the scalp, tears trailing down her cheeks. Her classmates silently watch her walk into the classroom, visibly distressed. Meanwhile, the Filipino-Ghanaian girl walks in with a calm demeanor, her hair neatly styled in a high bun.

As the class gathers around their sobbing classmate, she explains in a trembling voice that the headmaster had given her a choice: cut her hair or face punishment. But the other girl had simply been told to tie hers back. The disparity was blatant.

This is not a fictional story. It is a real event I witnessed.

Outdated Rules, Unequal Enforcement

In many African Senior High Schools (SHS), particularly public institutions, female students are still routinely required to cut their hair. These policies, rooted in colonial-era ideologies, are often justified with reasons like discipline, uniformity, and hygiene.

Yet, there's a troubling inconsistency in how these rules are enforced.

Foreign girls—particularly those with lighter skin tones or visibly mixed heritage—are often allowed to braid, tie, or style their hair neatly. In contrast, African girls are required to cut theirs completely. This double standard raises a pressing question: How does enforcing different rules for different skin tones promote discipline or uniformity?

Colonial Shadows and Cultural Insecurity

The issue is a byproduct of deep-rooted colonial attitudes that framed African features like natural hair as unruly, messy, or unmanageable. Such terms, laced with prejudice, continue to linger in school policies and social norms.

By forcing young African girls to cut their hair, we send them a harmful message: that their natural features are less acceptable than those of their peers.

Though some defend this rule as temporary, saying hair grows back, the emotional and psychological damage begins early. Many young women leave high school unable to embrace their natural hair, resorting to chemical relaxers and heat styling to conform to a beauty standard that is not their own.

Schools Must Foster Identity, Not Suppress It

Educational institutions play a pivotal role in shaping a student’s sense of identity, self-worth, and confidence. Enforcing unequal grooming policies only teaches young African girls that they must suppress parts of who they are to fit in.

This must change.

Schools can maintain neatness and discipline while also respecting diversity. Policies should be updated to allow clean, natural hairstyles such as braids, cornrows, twists, or low afros. These are culturally significant, easy to maintain, and empower girls to express themselves confidently.

Equality Starts with Policy

The African girl is no less deserving of respect than her lighter-skinned or foreign classmates. Her hair is not a distraction, nor is it a problem to be fixed. It is a crown—one that should be celebrated, not shaved off in shame.

It’s time for African schools to rethink outdated hair policies. The classroom should be a space of inclusion, empowerment, and equality, not one where a girl's identity is conditioned on the texture of her hair.

Let our schools lead the way in dismantling systemic biases. Let’s teach our daughters that they are enough just the way they are.

Nhyi

Nhyi